AI: Beware False AI Reflections

...they’re just tools for work & play

My short description for this newsletter over 120 daily posts ago made clear that I’m a long-term optimist on AI technologies, which are just getting started after decades of work:

“AI is coming. Ready or not. This explores the glass half full. By a seasoned Tech Explorer. “

The half-empty part of the glass that worries me the most is that regular people overly connect emotionally with AI. People seeing human-like characteristics reflected back. Anthropomorphizing AI, to use the fancy word for it. Believing that AI is listening to them, and connecting with them. Forgetting that it’s just software even when dressed up as human-like digital avatars, and someday humanoid looking robots.

As companies large and small spend billions to make AI more ‘real’ than ever, this is a risk none of us can ignore.

What brought this home again was this episode highlighted by Business Insider:

“OpenAI is rolling out a new voice feature for ChatGPT over the next two weeks, which will put an AI voice companion in the pockets of people seeking a more human conversation with the chatbot.”

“There's one thing it probably shouldn't be mistaken for: an on-the-go therapist. OpenAI, however, doesn't seem to have any qualms with users opening up ChatGPT for a heart-to-heart.”

“On Tuesday, Lilian Weng, head of safety systems at OpenAI, wrote on X that she ‘just had a quite emotional, personal conversation’ with ChatGPT in voice mode. She said she talked to it about the mental strains that come with a high-flying career, including stress and maintaining a work-life balance.”

"Interestingly I felt heard & warm. Never tried therapy before but this is probably it? Try it especially if you usually just use it as a productivity tool," Weng wrote.”

“Her experience was amplified by OpenAI president, chair, and cofounder Greg Brockman, who reposted the anecdote on X and said, ‘ChatGPT voice mode is a qualitative new experience.’”

As amazing as AI technologies are, they’re not therapists. Just tools to help us be better, and do better. A number of smart folks have been emphasizing this for a while. It’s good to visit and re-visit them. This piece “Chatbots are not People’Designed-in dangers of human-like AI Systems”, is a particularly good start.

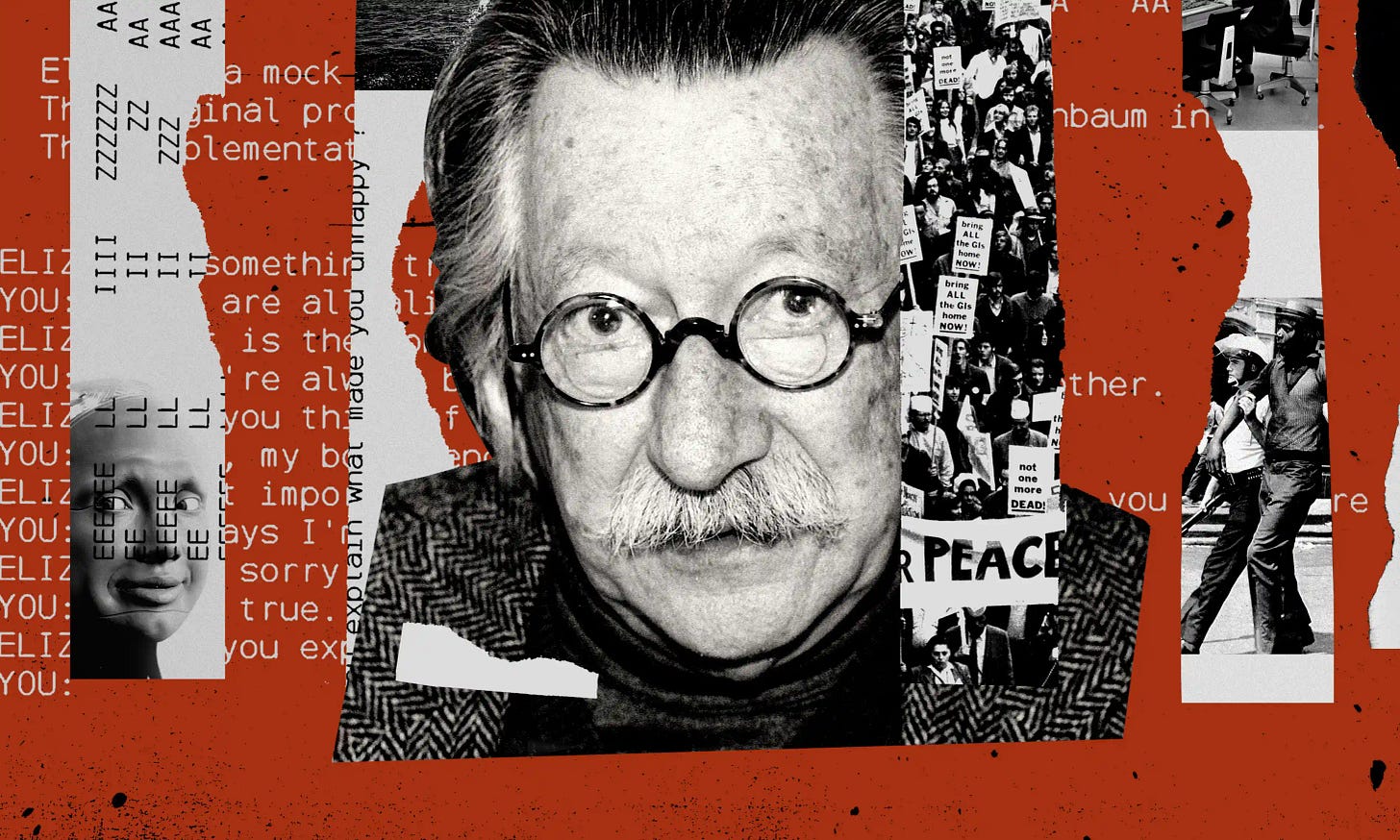

There’s a haunting story going back to the dawn of AI and machine learning, all the way to 1966 that bears re-telling. As the Guardian recounts:

“Weizenbaum’s nightmares: how the inventor of the first chatbot turned against AI”.

“Computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum was there at the dawn of artificial intelligence – but he was also adamant that we must never confuse computers with humans.”

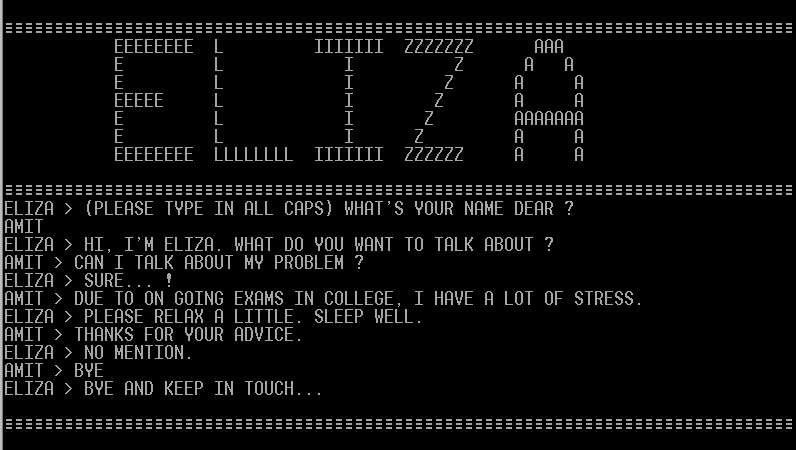

“In 1966, an MIT professor named Joseph Weizenbaum created the first chatbot. He cast it in the role of a psychotherapist. A user would type a message on an electric typewriter connected to a mainframe. After a moment, the “psychotherapist” would reply.

User: Men are all alike.

Chatbot: IN WHAT WAY

User: They’re always bugging us about something or other.

Chatbot: CAN YOU THINK OF A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

User: Well, my boyfriend made me come here.

Chatbot: YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

User: He says I’m depressed much of the time.

Chatbot: I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED

“Weizenbaum published this sample exchange in a journal article that explained how the chatbot worked. The software was relatively simple. It looked at the user input and applied a set of rules to generate a plausible response. He called the program Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion.”

Yes, that famous Eliza. The one that started it all, the nightmare and the seductive promise of AI. The piece goes on:

“Eliza isn’t exactly obscure. It caused a stir at the time – the Boston Globe sent a reporter to go and sit at the typewriter and ran an excerpt of the conversation – and remains one of the best known developments in the history of computing. More recently, the release of ChatGPT has renewed interest in it. In the last year, Eliza has been invoked in the Guardian, the New York Times, the Atlantic and elsewhere.”

“The reason that people are still thinking about a piece of software that is nearly 60 years old has nothing to do with its technical aspects, which weren’t terribly sophisticated even by the standards of its time. Rather, Eliza illuminated a mechanism of the human mind that strongly affects how we relate to computers.”

It connects directly to where we are today, at the threshold of billions of hyper-scaled Elizas for us all:

“Weizenbaum had stumbled across the computerized version of transference, with people attributing understanding, empathy and other human characteristics to software. While he never used the term himself, he had a long history with psychoanalysis that clearly informed how he interpreted what would come to be called the “Eliza effect”.

“As computers have become more capable, the Eliza effect has only grown stronger. Take the way many people relate to ChatGPT. Inside the chatbot is a “large language model”, a mathematical system that is trained to predict the next string of characters, words, or sentences in a sequence. What distinguishes ChatGPT is not only the complexity of the large language model that underlies it, but its eerily conversational voice. As Colin Fraser, a data scientist at Meta, has put it, the application is “designed to trick you, to make you think you’re talking to someone who’s not actually there”.

The whole piece is well worth reading, for more than historical reasons. The cautionary aspects of the Eliza tale are worth remembering this week particularly, as Meta launched personalized AI ‘Smart Agents’ for the three billion souls using Meta properties worldwide. With Google, OpenAI, Microsoft, and dozens of well-funded AI companies large and small also doing the same. With ‘Digital twins’, ‘Universal Translators’, Smart Assistants at work, and so much more around the corner.

We are at the threshold of some really net good things that will come out of this AI thing. It will take more time than we think. All the way there, we need to keep reminding ourselves: “It’s just a tool…to learn, create, help us reason, entertain ourselves, and overall be better humans.’ Especially when it seems ‘magical’, with ‘emergent’ capabilities of ‘intelligence’ and ‘empathy’. But the machines themselves are NOT anywhere close to the human ability to emote. One of the many things that make us human. Stay tuned.

(NOTE: The discussions here are for information purposes only, and not meant as investment advice at any time. Thanks for joining us here)